Submitted by Jane Durkin on Thu, 09/10/2025 - 16:32

2025 marks 200 years since John Stevens Henslow (1796-1861) became Professor of Botany and went on to revitalise the study of plants at the University of Cambridge.

He was elected fourth Professor of Botany in 1825, taking an oath before the Vice Chancellor as 'King's Reader in Botany' on 10 October that year. He held the position for 36 years until his death in 1861.

Revitalising botany

Henslow had a significant impact on botany at Cambridge, particularly in revitalizing the subject and inspiring future generations of botanists, including Charles Darwin.

His knowledge of entomology and mineralogy also led to a rejuvenation of teaching and research in natural history more generally.

He introduced innovative teaching methods, including practical classes in the Botanic Garden and local countryside, making the study of plants more accessible and engaging.

Henslow’s botanical lectures were extremely popular, inspiring generations of naturalists to travel the globe and send specimens for the Cambridge University Herbarium.

The techniques Henslow developed brought botanical teaching into the modern age and under his watch botany became part of Cambridge’s Natural Sciences Tripos in 1851.

Mentor to Charles Darwin

Henslow is perhaps best remembered as a friend and mentor to Charles Darwin (1809-1882), inspiring him with a passion for natural history and proposing him to sail on the HMS Beagle as the naturalist on its 1830’s five-year voyage.

He encouraged Darwin to study plant diversity and variation, which played an important role in Darwin's development of his theory of evolution.

Botanical specimens from Darwin’s voyages – part of the empirical evidence behind the theory of natural selection – are still housed in the Cambridge University Herbarium. Many are now accessible online as part of the Herbarium's recent digitisation project.

Henslow also helped promote Darwin’s work, including publishing the ‘Beagle Letters: Extracts From Letters Addressed to Professor Henslow by C. Darwin, Esq.’ through the Cambridge Philosophical Society in 1835.

Cambridge University Botanic Garden

Henslow was instrumental in the relocation of the Cambridge University Botanic Garden to its current site.

The original Botanic Garden was in centre of the city – now the University’s New Museums site.

Henslow convinced the University to move its Botanic Garden from the cramped city centre location to the current 40-acre site. The garden was re-founded there in 1846 on the academic principle of being provided for the study of plants.

The new garden was organised according to the natural systems of classification using the most up-to-date botanical research methods of the time. It was laid out in the popular ‘Gardenesque’ style, creating a beautiful landscape to house the specimen plants.

The trees that are central to the collection were planted in groups to demonstrate the variation that can occur within species due to hybridisation and mutations – or ‘monstrosities’ as Henslow described them.

Today the garden’s Living Collection holds over 8,000 plant species and continues to support scientific research within the University and around the world. The garden also now welcomes over 350,000 visitors a year to explore the amazing world of plants with learning programmes, community schemes, school visits, trails and tours.

Cambridge University Herbarium

Henslow also expanded and reorganized the Cambridge University Herbarium, adding over 10,000 specimens and establishing it as a valuable resource for research.

Henslow’s herbarium specimens record his fascination with variability and discontinuity within and between species, an approach which had an important influence on his most famous pupil, Charles Darwin.

Many specimens came from students who Henslow actively encouraged to embark on global voyages. In addition to Darwin’s voyage on the HMS Beagle, Henslow’s students took clerical positions across the British Empire and served on East India Company voyages, collecting specimens across Asia, Oceania, the Pacific, Africa and the Americas.

The Herbarium began when the second Professor of Botany John Martyn (1699-1768) gave his ‘Hortus Siccus’ (literally ‘Dry Garden’) and botanical library to the University in 1762.

Henslow took it under his wing and painstakingly remounted over 3,000 early specimens, added over 3,500 of his own, and acquired many further specimens through his extensive connections within the British scientific community.

"Building a world-class herbarium was central to Henslow's research and teaching at Cambridge – gathering a global collection to better understand the extent, utility and diversity of God's creation. Henslow recommended many positions on global voyages – perhaps the most well-known being Charles Darwin's participation in the voyage on HMS Beagle between 1831 and 1836," explains Dr Edwin Rose, Bye-Fellow of Darwin College Cambridge and Early Career Fellow at the University of Leeds.

"When teaching and building the Herbarium, Henslow employed innovative printed technologies ranging from wallcharts to printed pamphlets asking correspondents and travellers to send specimens. Many proved fundamental in revising both research and teaching practices in nineteenth-century Cambridge – a reason for the inclusion of Botany, including plant physiology and vegetable anatomy, as part of the new Natural Sciences Tripos in 1851," he says.

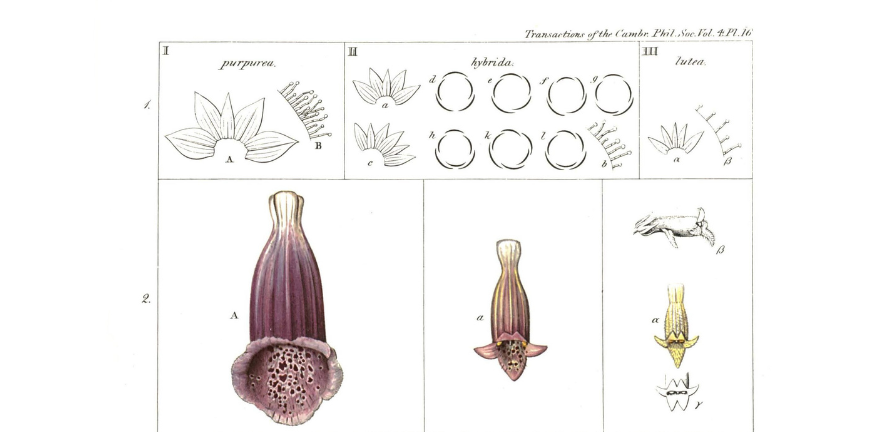

‘On the Examination of a Hybrid Digitalis, 1831’ – another publication from the Cambridge Philosophical Society – demonstrates Henslow’s pioneering approach to the use of botanical illustrations, which are best seen in his range of over 100 colourful botanical wall charts and diagrams that were used for teaching his students.

Today, the herbarium is housed in the Sainsbury Laboratory, next to the Botanic Garden. Outside the entrance stands a marble bust of Henslow by the sculptor and poet Thomas Woolner, one of the founder-members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Founding the Cambridge Philosophical Society

Henslow co-founded the Cambridge Philosophical Society in 1819, along with Adam Sedgwick and Edward Clarke, with the aim of promoting scientific research and inquiry.

In 2010 the Cambridge Philosophical Society launched its Henslow Fellowships in the fields of Natural Science, Engineering, Mathematics, Computer Science and Clinical Sciences, in honour of Henslow as co-founder.

Henslow died at Hitcham in 1861 aged 65 and is buried in the churchyard there. His portrait hangs in the church. Following his death, Charles Darwin wrote of him: "I believe a better man never walked this earth".

Henslow Circle Patrons Group – Cambridge University Botanic Garden

Henslow’s support of the Botanic Garden is also continued by the Garden’s patrons, members of the Henslow Circle. Henslow Circle Patrons enjoy a unique relationship with the Garden, as well as exclusive events and activities. For more information about the programme, please visit Henslow Circle Patrons Group - Cambridge University Botanic Garden or email development@botanic.cam.ac.uk.

Read more:

- Rarely seen 200 year-old plant specimens Darwin sent from Voyage of the Beagle on display for new TV show

- John Stevens Henslow, Cambridge Philosophical Society co-founder

Image: Section of a plate from ‘On the Examination of a Hybrid Digitalis, 1831’ published by Cambridge Philosophical Society.