In the 21st-century Department of Plant Sciences, specialists in rainforest ecosystems rub shoulders with molecular geneticists, and students hear lectures by experts in epigenetics before examining biodiversity in the University Botanic Garden. This exceptional breadth results from the very prolonged development of botany as an academic subject in Cambridge.

Botanical teaching and research in Cambridge dates from the time of William Turner, whose New Herball of 1551-1568 records the botanical features of 238 plants native to England, and marks the beginning of plant systematics and taxonomy in this country. Turner and his colleagues studied plants with a view to elucidating their pharmaceutical properties – a powerful impetus that still lies behind much of today’s research.

The guiding genius in the development of Cambridge botany was John Ray, one of the energetic English Renaissance scholars who established natural science as a field worthy of academic study. Ray was passionate about botany, and searched the University for someone to instruct him:

"But, to my astonishment, among so many masters of learning and luminaries of letters I found not a single person who was deeply versed in Botany, and only one or two who had even a slight acquaintance with the subject...so why should not I, endowed with ample leisure, if not with great ability, try to remedy this deficiency...?"

Thus determined, Ray shored up Cambridge botany by giving instruction himself and by publishing seminal material, including the first flora of Cambridgeshire (1660) and of England (1670). Botany, like other natural and experimental subjects, languished in the 18th century, although, curiously, the first Professor of Botany, Richard Bradley, was appointed in that century, in 1724. His successors were John Martyn, and then his son Thomas Martyn, who recognised the importance of the Linnean system of nomenclature; he is also remembered, along with the benefactor Richard Walker, as a founder of the Botanic Garden, which became an early site for experimental botany.

The election of John Stevens Henslow, with his knowledge of entomology and mineralogy, to the Chair of Botany led to a rejuvenation of the subject, so that it came to encompass the whole of natural history. This accounts for Henslow’s crucial influence on his most famous pupil, Charles Darwin. Botanical specimens from Darwin’s voyages – part of the empirical evidence behind the theory of natural selection – are still housed in our Herbarium.

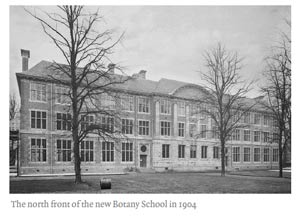

Our present home on the Downing Site was established in 1904 through the extraordinary scientific and administrative ability of Harry Marshall Ward, whose interest in German scientific advances and experience of practical forestry are examples of the international co-operation that is still such an important part of life in the contemporary Department.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the new subjects of genetics and ecology were coming into their own. The development of modern British ecology was shaped by AG Tansley, who combined taxonomic and experimental approaches to the study of vegetation. There was also diversification into bryology, the study of mosses; mycology, the study of fungi, and also the quaternary sciences: the latter have helped to show how the earth’s climate has changed. Physiological studies by FF Blackman and GE Briggs made significant contributions to our understanding of photosynthesis and ion transport.

Since the 1950s we have seen the rise of plant pathology and plant biochemistry, followed by molecular and cell biology, with Enid MacRobbie’s work on the ionic relations of cells and the mechanisms of stomatal opening, and studies of starch and sucrose metabolism by Tom ap Rees. In 2007, David Baulcombe, who made key discoveries about RNA and epigenetics, was appointed as Professor of Botany. We were honoured that Her Majesty the Queen chose to confer the title of Regius Professor on the Chair of Botany in 2009, the 800th anniversary of the founding of the University of Cambridge.

The founders of botanical science would not recognise many of the methods and techniques employed by modern plant scientists, but without their pioneering work on naming and classification, and their early experiments on the function, structure and growth patterns of plants, no current work at the molecular level – which enables us to make advances in the breeding and conservation of plants – would be possible.