Sir David Baulcombe, 15th Professor of Botany at the University of Cambridge, looks at the role of Richard Bradley, first Cambridge Professor of Botany, and London gardener, Thomas Fairchild, in the history of hybridisation in plants.

Richard Bradley – the first Cambridge Professor of Botany – had several problems. He lived in an age when Professorships were not salaried and, lacking personal wealth, he ended up in a cycle of constant debt. To make money he became an eighteenth-century equivalent of Monty Don, Bob Flowerdew and Delia Smith.

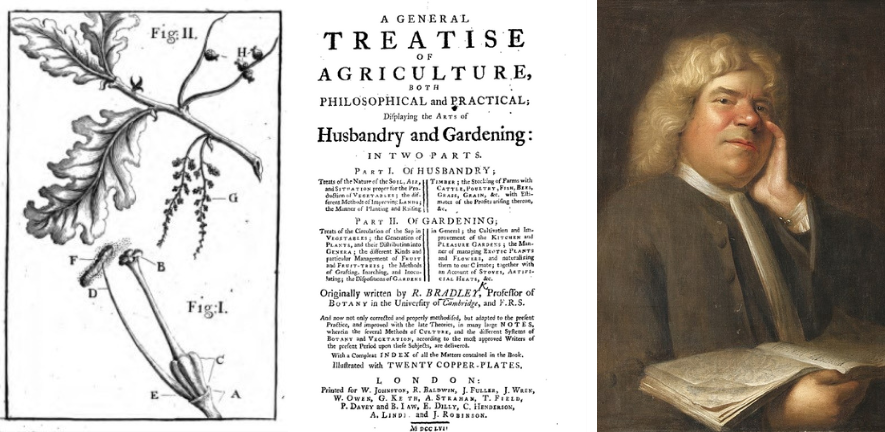

His publications include 'A Treatise of Agriculture both philosophical and practical displaying the arts of husbandry and gardening' and 'The Country Housewife and Lady’s director in the management of a house and the delights and profits of a farm'. His red bean ketchup was highly regarded. This work may have provided income, but it did not help his credibility as a serious academic. ‘Plus ca change’ for scientists reaching out to the general public.

He also used more nefarious means to fill his purse and spent some time in the Netherlands where he posed as a medical doctor (without having the qualifications) wearing a black wig and under a pseudonym. Apart from money, one of Bradley’s other problems was John Martyn who also wanted to be the Cambridge Professor. Martyn’s response to being overlooked was to troll Bradley in a dubious rag known as the Grub Street Journal. Martyn accused Bradley of neglecting his students and failing to raise cash for a Cambridge Botanic Garden but these reports could be motivated by jealousy.

Unfortunately, the tittle-tattle distracts from the fact that Bradley was a serious botanist. One of his useful contributions was that he drew attention to the work of Nehemiah Grew and Marcello Malpighi. These two botanists working in England and Italy were greatly admired by Cambridge botanist Agnes Arber who we are celebrating this year alongside the 300th anniversary of the Cambridge Professorship. Arber was a brilliant plant morphologist who built on the legacy of Grew and Malpighi in many aspects of her work on plant anatomy, including their description of reproductive structures.

Their insightful analysis led to the idea that there is sexual reproduction in plants as with animals, and this idea was reinforced in 1694 by the German physician Rudolf Camerarius. Until then, the pollen was thought to trigger the development of the fully formed embryonic plant in the flower. Bradley played an important role in reinforcing the idea of sexual reproduction by introducing Thomas Fairchild to the scientific establishment.

Fairchild was an ingenious nurseryman from Hoxton near London who was always looking for new plant material for his clients. He was well known to Bradley and, in ‘Of the Generation of PLANTS’ (1717) , Bradley described Fairchild’s demonstration that “the Farina [pollen] of Carnation [Dianthus caryophyllus] and Sweet William [Dianthus barbatus] will impregnate the other and that the Seed so enliven'd will produce a Plant different from either ….a Plant neither Sweet William nor Carnation, but resembling both equally.” As far as I am aware, this was the first formal recognition in a plant that both parents contribute to the morphology of the progeny. The hybrid plants were known as Fairchild’s mules and they are preserved in the Oxford University herbarium.

Fairchild’s findings were read to the Royal Society although he was not a Fellow, and it is likely that they contributed to the eventual understanding of sexual reproduction in plants. This thinking influenced Linnaeus and, of course, it blossomed in Mendel’s monastery garden. Fairchild’s mule is also a reminder that hybridisation occurs between species and is an important process in evolution of plant and animal genomes. Humans, for example, hybridised with neandertals and bread wheat is a hybrid of three species.

Hybridisation in plants has been a recent focus of the fifteenth Professor of Botany and the connection with Arber, Bradley and Fairchild shows how understanding in science emerges slowly. Knowing about the history of our subject may provide useful direction for current research and in that spirit, in this anniversary year, you may find inspiration in the history of the Department in the 20th century by Grubb, Stow and Walters (see below).

References

The Ingenious Mr. Fairchild: The Forgotten Father of the Flower Garden Hardcover – January 1, 2001 by Michael Leapman (author) ISBN-13: 978-0312276683

Žárský, V., and J. Tupý. 1995. 'A Missed Anniversary: 300 Years after Rudolf Jacob Camerarius’ ‘De Sexu Plantarum Epistola’'. Sexual Plant Reproduction 8 (6): 375–76. doi:10.1007/BF00243206.r

Williamson, R. 'John Martyn and the Grub Street Journal, with particular reference to his attacks on Richard Bentley, Richard Bradley and William Cheselden.' Med Hist. 1961 Oct;5(4):361-74. doi: 10.1017/s002572730002665x. PMID: 14007254; PMCID: PMC1034654.

The Country Housewife, Richard Bradley and Crisp Fried Quail. An entertaining account of 'The Country Housewife' and I will certainly be trying out some of the recipes.

Arber, A. 'Nehemiah Grew (1641-1712) and Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694) An Essay in Comparison” Isis (1942) Vol. 34, No. 1 pp. 7-16

Grubb, P.J., Stow, E.A, and Walters, S. M. '100 Years of Plant Sciences in Cambridge: 1904–2004'

Images from left to right: the sexual structure of plants explained from Richard Bradley’s 'New Improvements of Planting and Gardening'; title page from Richard Bradley's 'A General Treatise of Agriculture'; portrait of Thomas Fairchild, Art UK, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.